By Hank Burdine

In 1910, the Fine Cotton Spinners and Doublers’ Association of Manchester, England, was a big English syndicate consisting of over fifty cotton milling companies that depended on long staple cotton from Egypt to supply their mills for their production of thread, yarn and cloth that was shipped worldwide. It soon became apparent that Egypt was about to run through a string of slim years and the huge conglomerate began to look around for other sources of the specific cotton that they needed for their mills. Soon their eyes were set on the Mississippi Delta. The boll weevil hadn’t yet reached our Delta, but there were fears that the invasion was eminent and land prices began to fall. It wasn’t long before a contingent of directors from the F. S. A. came over to look and see what opportunities were here to assure them a steady and secure source of long staple cotton.

In 1910, the Fine Cotton Spinners and Doublers’ Association of Manchester, England, was a big English syndicate consisting of over fifty cotton milling companies that depended on long staple cotton from Egypt to supply their mills for their production of thread, yarn and cloth that was shipped worldwide. It soon became apparent that Egypt was about to run through a string of slim years and the huge conglomerate began to look around for other sources of the specific cotton that they needed for their mills. Soon their eyes were set on the Mississippi Delta. The boll weevil hadn’t yet reached our Delta, but there were fears that the invasion was eminent and land prices began to fall. It wasn’t long before a contingent of directors from the F. S. A. came over to look and see what opportunities were here to assure them a steady and secure source of long staple cotton.

According to a March, 1937 article in Fortune Magazine, a Michigan land promoter named Lant K. Salsbury had options on thousands of acres of good Delta dirt from Rosedale banker and planter, Charles Scott. During the winter of 1911, the two took the Englishmen goose hunting on the Mississippi River and showed them around the Delta, especially the vast acreage that Scott had accumulated around Scott, Mississippi at a great bend in the River. The headwaters of Deer Creek came out of an old meander bend in an oxbow known as Lake Bolivar. The land was fertile beyond belief. “With sport and salesmanship” leading the push, the majority of the Englishmen were impressed. Herbert W. Lee, who became President of F.S.A., wasn’t impressed and later stated “they dug some goose pits and we fell into them!” At the end of the day, however, the Fine Spinners Association paid $3,000,000 (averaging $95 per acre) and later an additional $1,500,000 for more land, clearing and draining it and building tenant cabins on 38,000 acres of the most fertile dirt on earth. Included in this total acreage was a 4,500 acre farm on Deer Creek at Estill, Mississippi.

The deal consisted of several land holding companies and an operating company. Because of a Mississippi State law prohibiting any agricultural operation to consist of over 10,000 acres, unless the corporation had been chartered between 1886 and 1889, a legally chartered land speculation company called Delta & Pine Land Company, incorporated in 1886, was bought and the three operating companies merged into it. Mr. Salsbury, the original deal promoter, was put in charge of the entire operation and cotton planting began in earnest. However, before the best ground could be planted that first year, the Mississippi River rose and seeped under the levees eventually overtaking them on the 20 mile stretch of the western boundary of the farm. The first year’s crop was a disaster producing only 2,800 bales of cotton. And then, the boll weevil struck. Between the boll weevil and periodic flooding, the Englishmen did indeed begin to believe that they had “fallen into some goose pits!” Through diligence, crops were planted and picked and the largest cotton plantation in America continued to barely survive.

In 1919, with a bumper crop picked, the price of cotton soared to 85 cents a pound and Mr. Salsbury cleared his accounts with his sharecropping tenants and with the steadily rising price of cotton, decided to hold on to his share of the cotton before selling in hopes of making a “fabulous killing”. Mr. Salsbury was still holding D&PL’s share of the crop in the spring of 1920 when the price began to drop down to 15 cents a pound. The great crop of 1919 was later sold at 6 cents a pound bringing a potential $3,000,000 profit down to a $1,000,000 loss. From 1912-1927 the British ownership had invested $4,500,000 initially and plowed another $3,000,000 into the dirt and received a dividend only in 1920. “They had taken a large segment of the Mississippi Delta and were stuck with it.” Goose pit, indeed!

The group of Englishmen comprising the Fine Spinners Association was as conservative a bunch of business chaps as could sit around a board table. Fifteen years of the Mississippi River flooding their land and the invasive boll weevil gnawing on their cotton crop was just about all they could take. Destiny, however, was soon to come knocking in an around about way. Possibly looking for a way out of the “goose pit” he now found himself in, Mr. Salsbury put together his largest promotion ever which “dwarfed D&PL and included it (if it could be bought).” One of the bankers involved in promoting the massive venture was a Mississippi banker named Oscar Johnston. Mr. Johnston went to England to trade for options to buy D&PL and was successful. The Englishmen were finally seeing a way out of their deepening dilemma. “On the very day in October, 1926, when the new super plantation deal was to be floated, the cotton market broke and the promoters decided to wait awhile.” And they were still waiting in the spring of 1927 when the Mississippi River broke through the levee at Mounds Landing, two miles from the D&PL headquarters at Scott starting the worst flood disaster ever to hit the United States. Every acre D&PL owned was inundated. But by this time, Mr. Salsbury, with even greater and grander schemes in mind, had already resigned his presidency at D&PL. FSA had been so impressed with Mr. Oscar Johnston and his abilities; they had hired him to take over the operation.

However, no crop could be planted in 1927, and the goose pit seemed to be caving in on the Englishmen’s heads. The plantation lost 1,250 acres to erosion and the necessity of relocating the levees. Several thousand acres were covered with sand and unfit for a cotton crop. Over 100 homes were destroyed and 100 mules drowned. Flood damage was estimated at over $500,000. However, the black clouds had a silver lining, indeed. The new president/banker Oscar Johnston foresaw a flood season shortage of cotton and began playing the cotton market making $200,000 towards the rehabilitation of D&PL. In the following 9 years of operating D&PL, Oscar Johnston produced a six-year total profit of $1,745,000 as opposed to a three-year loss of $595,000. The Englishmen were out of the goose pit even though it was the middle of the Depression.

However, no crop could be planted in 1927, and the goose pit seemed to be caving in on the Englishmen’s heads. The plantation lost 1,250 acres to erosion and the necessity of relocating the levees. Several thousand acres were covered with sand and unfit for a cotton crop. Over 100 homes were destroyed and 100 mules drowned. Flood damage was estimated at over $500,000. However, the black clouds had a silver lining, indeed. The new president/banker Oscar Johnston foresaw a flood season shortage of cotton and began playing the cotton market making $200,000 towards the rehabilitation of D&PL. In the following 9 years of operating D&PL, Oscar Johnston produced a six-year total profit of $1,745,000 as opposed to a three-year loss of $595,000. The Englishmen were out of the goose pit even though it was the middle of the Depression.

Oscar Johnston was able to produce this remarkable turnaround by expert management skills on some of the best land in the world. One of the first things he did as president of D&PL was to get all of his sharecroppers on a half share. The cropper supplies his labor and nothing else. D&PL supplies him with a good cabin, cottonseed, mules and his tools. At the company store, the cropper had an account where he charged his food, clothing and other necessities. The cropper was also responsible for half of the cost of fertilizing and boll weevil poisoning. At the end of the year, when the cotton was picked, the accounts were settled and the books cleared. D&PL kept their half and the cropper kept whatever was left over after his debt at the company store was taken out and his half share of poisoning and fertilizing. He also kept half of the corn crop he had planted.

A typical sharecropper plot consisted of about 15-28 acres, including a one-acre house site, garden and 2-5 acres for corn and the rest planted in cotton. He cuts company timber for firewood to heat his house and cook with in his wood stove. Farming about 125 days a year, a cropper spends his working day from “can ‘til can’t” busting ground, rowing, planting, chopping and picking cotton. On good dirt and in a good year, a D&PL cropper could pick almost 20-30 bales of cotton from his plot. A typical tenant at settlement time could make around $1,000 a year, $480 in credit at the company store and $520 in cash on settlement day.

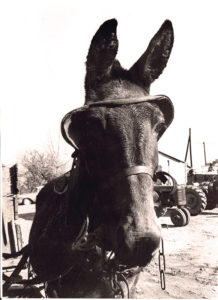

Oscar Johnston knew that to have a successful operation he had to have the best of everything. He already had the best land money could buy (I remember an old saying that “The Lord could have made better dirt than Deer Creek, but He figured He just didn’t need to.”) He had the best livestock, 1,000 fine and strong mules scattered in ten barns where they returned home to fresh water, good hay and grain. These mules were cared for by special hostlers under the direct supervision of Mr. Mac McClure “an elderly Scot who has money of his own, but likes to work on the biggest mule farm in the Cotton Belt simply because he likes mules.” The mules are picked up each morning and delivered back each night and are constantly cared for. And he had the best tenants farming his land. With a turnover rate of only 10-12% a year, a sharecropper position at D&PL was sought after and was indicative of the satisfaction of the labor. One study prepared on farm labor in the South gave Mr. Johnston credit for “administering his contracts better than any other planter studied.”

The model plantation was run through the expert supervision of twelve separate unit managers who met four times a year in a round table meeting to discuss their farming operations, needs and changes. Each manager supervised about 100 sharecropper families on 1,000-1,200 acres of cotton land with the tenant cabins about a half mile apart. Carson, Dixon, Belmont, Fox, Triumph, Lake Vista, Isole, Salsbury, Nugent, Young and Lee were all located around Scott, with Empire almost 30 miles away at Estill. The managers spent their days on horseback riding their respective units and visiting with as many of the croppers as possible, directing the cotton growing techniques and persuading them to do their own gardening. Many of the sharecroppers also had hogs and cows and chickens to supplement their gardens.

In 1937, the cotton grown on D&PL was some of the finest in the South. Dr. Early C. Ewing was plant breeder at D&PL and was an expert in developing cotton seed that became famous worldwide. Trained at Mississippi State College and Cornell before hiring on at Mississippi State Experiment Station at Stoneville, then moving to D&PL, Dr. Ewing developed a seed that matured early and gave a good staple but also gave a remarkably high lint to seed ratio. Delta and Pine Land sold more cotton seed to other planters than any other world agency. The cotton was ginned in three separate cotton gins and shipped out on the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad. D&PL’s cotton was marketed and sold through Staple Cotton Cooperative Association and the reputation so high that the cotton was contracted long before it was ever picked.

Because of the fact that the boll weevil would eat up a late maturing cotton crop, which produced the extra long staple cotton for which the Fine Spinners Association bought 38,000 acres of Delta land, not one bale of cotton was ever shipped overseas to England. All Delta & Pine Land cotton stayed right here in America. Oscar Johntson had floated into Scott, Mississippi on the back of the 1927 flood, but within 10 years, through expert management techniques, dedicated labor, the best of mules and some of the finest dirt in the world, dug a bunch of disheartened Englishmen out of a deepening goose pit and gave them a very profitable cotton operation, right in the heart of the Mississippi Delta.